Remembrance and Resistance at the KU Memorial Union

Almost 100 years after the end of World War I, two of the busiest stops on KU’s campus remain a memorial to those who died. Now, 80 years after its completion, a look at KU Memorial Union.

By Darby VanHoutan

It’s noon on a Wednesday, and almost 80 years after this space first opened it’s doors, its packed wall-to-wall for orientation with sweaty students wearing name tags, clutching their class schedules with their parents in tow. Two floors above them, hanging on the wall, are the pictures of 129 students and alumni for whom the Memorial Union — the building in which they’ve spent practically the entire day — was built.

They may not have noticed the myriad plaques and posters surrounding them or even the name of the building they’re standing in, but these students are in a World War I memorial. One of two memorials to World War I on campus, the Memorial Union serves as a non-stop place for countless activities, speeches, naps, lunches, protests, and, as many of its patrons likely don’t realize, a way of paying tribute to KU students and alumni that died in World War I.

Early Years

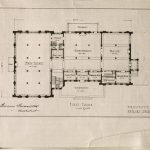

On May 10, 1920, a group met for the first time to discuss the construction of what would become the center of campus, the home to numerous student groups, the chambers for Student Senate, the location of a massive arson during civil rights and war protests, and ultimately, a “home away from home.”

This group was the Memorial Corporation and it was established as a result of the “Million Dollar Drive” that was held to raise funds for three World War I memorials on campus.

According to KU History, several ideas were tossed around before they settled on the memorials we have today. Things like an archway to campus and a grove of trees were put aside and instead, they decided on a new football field and student union.

And, although not a monument to any war, they also erected a statue of the first dean of the law school, Jimmy Green. This statue currently stands outside of Lippincott Hall and was sculpted by Daniel Chester French — the same man that sculpted the statue of Abraham Lincoln that currently sits in the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C.

Howard Graham, who currently serves as associate director of Academic Programs in the Office of First Year Experience, has studied the “Million Dollar Drive” extensively for his research into Memorial Stadium. The “Million Dollar Drive,” Graham says, was successful because of the stakeholders that continued to push for it.

“It’s really an alumni and student driven campaign that the administration and faculty are also involved with and behind,” Graham said. “I don’t think that it has the momentum it does without the alumni and the students involved.”

Memorial Stadium opened first on Nov. 11, 1922, exactly four years after Armistice Day and the end of the war. It replaced the University’s original athletic field, McCook field.

The union opened its doors completely in 1938. However, it broke ground in 1925 and on April 30, 1926, the cornerstone was laid. This cornerstone, which still stands, almost hidden, in a pillar of the Union today has inside of it a copper box filled with mementos related to the great war.

This time capsule was the beginning of what Lisa Kring, current director of building and event services for KU Memorial Union, described as something that was happening on most campuses at the time.

“The notion was and is, you just need a place, there needs to be what they call now sort of a ‘third place’ where students can build a community and they can be a community with the faculty and the staff,” said Kring.

At that time, however, and for several years to follow, the Union segregated African Americans and whites. Shawn Alexander currently works in the African and African American Studies department as a professor and director for graduate studies. Places like the soda fountain and cafeteria, Alexander describes, were among the many places on campus that were segregated.

“Originally African Americans couldn’t go to the cafeteria and then they created separate seating for African Americans and white students,” Alexander said. “Chancellor Lindley famously says that he thought the segregated seating was fine, the black seating was fine, that he would actually sit over there. He would try to justify it very much.”

The Union remained segregated for several decades, even amid protests and letters from influential characters like W.E.B. Dubois who called for responses from administrators such as Chancellor Ernest Lindley. The space also remained a place for civil unrest and activism.

1960 – 1970

The Memorial Union underwent several changes after its initial founding with the addition of more levels, a bowling alley, and introduction of student group offices littered throughout the building. These groups included the YMCA, YWCA, Student Senate which began in 1969, and KU Info — which started as “rumor control.”

Kathryn Nemeth Tuttle, who has held several position at the University as a professor, researcher, and administrator in the office of Student Affairs, began attending the University in 1968. Along with being an alumna herself, she has studied student activism and women’s issues at KU and other universities over the years.

Tuttle was at the University on April 20, 1970 — the night the Memorial Union infamously burnt down. At the height of protests against the ongoing Vietnam War and civil rights protests on KU’s campus hosted by the Black Student Union demanding things such as more African American professors, the Union suffered a large fire.

On the night of the fire, Tuttle was at Sellards Scholarship Hall where she lived. She remembers bringing donuts to the firefighters and volunteers who worked all night to salvage anything they could out of the burning Union. Ultimately, the Union suffered $1,029,099.19 in damage, according to University Archives. Those responsible were never caught.

“I think a longer term effect really was how KU was perceived,” Tuttle said. “We were always seen as this liberal baskin and now it was kind of a place of violence. Then that summer erupted into more violence. It’s not just one group causing it.”

Although — as illustrated by the still unsolved arson of the union — there was a large amount of demonstrations during this time, Tuttle describes the ways the Union served, and still does serve, as a place for a different kind of protest.

“I would place the context of activism within the Union not so much of people inside there holding signs,” Tuttle said.

Organizations like the YMCA and Black Student Union were instrumental in protests both in the form of posters and vocal protests, she said, but also sit-ins at segregated restaurants and at the Chancellor’s Office.

“When you just look at the list of groups that have their offices in the Union,” Tuttle said. “It’s important to think of those as the new activism, I think.”

Today

Today, the Memorial Union stands six stories high. A parking garage has replaced what was once a restaurant called “gaslight.” Now, on the north end, stands the Sabatini Multicultural Resource Center. The ballroom that was destroyed by the 1970 fire has been restored.

Currently, its engulfed by construction equipment as the fourth phase of the Jayhawk Blvd. construction — which began three summers prior — is underway.

This current phase of construction includes a complete renovation of the Union’s outdoor plaza, which was previously made of bricks and furnished with a few tables. After construction is finished in early August, the plaza will include a wrap-around wall of benches, more space and lighting, and pavers instead of bricks.

Although the plaza area is currently closed for this construction, it will be finished by the fall semester and final phase of Jayhawk Blvd. construction — near the intersection of 13th Street and Jayhawk Blvd. as well as the parking lot across from the union — will be completed in summer of 2019.

The recently announced budget cuts, Kring said, don’t directly affect the plaza’s construction because of the independence of the Union Corporation. The cuts effects, however, are still felt, according to Kring.

“The only reason the Union corporation is here is to serve the KU community so when the KU community has budget cuts and things like that,” Kring said. “We certainly feel that.”

Overall, the memorial aspect of the union has remained. On the fourth floor, in the back near the stairs is the plaque memorializing those 129 students and alumni who died in WWI.

Their pictures and names are on the sixth floor. Next to those plaques is information regarding William T. Fitzsimons who, according to KU History, was the first American casualty of the war. Fitzsimons died in 1917 at a French field hospital as a result of a German airstrike.

This history will remain, according to Kring, regardless of what the future brings.

“I would anticipate we’ll continue to keep our name and I think, when you have these older buildings that have a story, why would you want to eliminate the story?” Kring said. “You have to sort of figure out a way to have the name be representative of not only what the current needs are but also what the past brought.”